The Use of Climate Information in Colombia: Lessons Learned from Interdisciplinary Collaboration

A travelogue from a field trip in Colombia by two of the 2023 students.

Leaving the office and stepping into the field as an interdisciplinary research group is like starting to dance with a partner and not alone. Not only can you incorporate your individual technique, but you can work in tandem with your partner to learn, grow, and create a new form of dance. Throughout our research, we did just that.

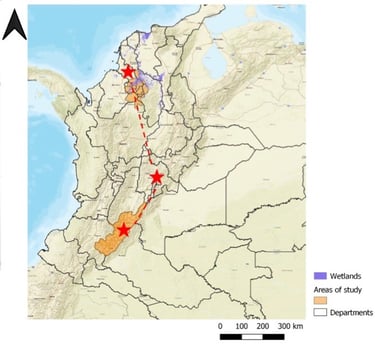

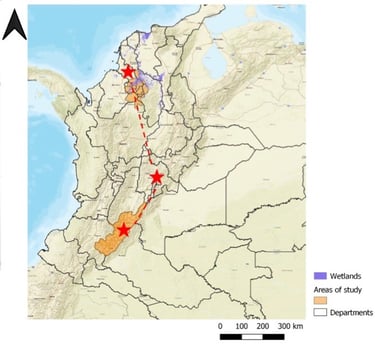

During the summer of 2024, Laurel DiSera and Carolina Hernández (CATER alumni ‘23), and Flora Lecomte* spent 3 weeks in Colombia conducting joint fieldwork to understand the local knowledge of climate and the use of climate information in two agricultural regions: in the mountains in the south (department of Huila), a coffee growing region, and in the lowlands in the north, a rice growing region.

* We are all Ph.D candidates, Laurel in climate sciences in Columbia University, Flora and Carolina in human geography in Sorbonne Nouvelle University (and also in National University of Colombia for Carolina). If you want to contact us, try here: Laurel DiSera: lad2192@columbia.edu; Carolina Hernández: carolina.hernandez@sorbonne-nouvelle.fr; Flora Lecomte: flora.lecomte@sorbonne-nouvelle.fr

This fieldwork was one of the methodological strategies of joint research that started at CATER school in Naivasha -without knowing it at the time. CATER was a privileged time for Laurel and Carolina to get to know each other, build trust, and share their research topics. During the school, they identified that they had mutual interests in 1) better understanding how people create knowledge about climate and 2) how different individuals valued scientific information in their day-to-day practices.

Right after CATER school the work started! Flora joined the research team, due to her extensive knowledge in the Huila region and interest in the project. The first step was to build a collective project from our own research. It took several conversations to reach agreements on the research questions, and more talks and readings to convey the best research strategy on the field. Scott Bremmer’s papers on the collective work in which he participated in Bangladesh were a major inspiration for our work.

Before heading into the field, we collectively formed a few questions to guide the interviews. First, to identify the understanding of climate in the different communities: 1) What climate cycles and climate events are remembered through personal and/or collective group memories, and what indicators are used to identify them? And 2) What does climate change mean to communities? Are the wetland (rice growers and fisher people) vs mountain (coffee growers) people experiencing similar or different effects of climate change?

Second, it was important to understand how communities were informed about the climate and how they interacted in response to it, leading to: 3) Where do community members receive their weather/climate information and how do they use it? And 4) What changes are the communities experiencing and how are they adapting?

We decided to confront these questions with the fieldwork in two different regions of Colombia. First, we spent a week in the department of Huila, in the south of the country, where we planned to meet coffee growers and fisher people. The Huila region is known for its micro-climates and thermal floors - or the changing climate zones as you climb up a mountain - from the valley of the Magdalena River to the high mountain ecosystems of páramos. As an agrarian department, Huila is now the largest producer of coffee of Colombia in quantity and quality and is also an important producer of cocoa, fruits and vegetables cultures. Additionally, Huila has two electric dams that were constructed in the 1980s and 2010s, which have impacted the fishing and climate in the area.

The second location of our fieldwork was the bio-geographical region of La Mojana, the interior delta of the Magdalena-Cauca rivers basin. In this region, we planned to meet fisherpeople, rice growers, and institutional actors in charge of the adaptation to climate change, as well as to conduct workshops with high school students. La Mojana is a region of wetlands and floodplains, regulated by the seasonal pulse of water from which communities have developed amphibious ways of life. Many changes, some intentional and not, to the landscape have occurred in La Mojana. For example, governments have attempted interventions to mitigate the “natural” floods by building flood walls, while rice and cattle production have inadvertently caused significant modifications to the territorialities of local communities through farming practices. More recently, the region has become more sensitive to climate change, experiencing catastrophic episodes of droughts and floods.

Mixed methods for complex topics and territories

Approaching subjects such as local knowledge of climate and the use of scientific information requires a methodological mix. We performed 17 in-depth interviews with different types of actors (tables 1 and 2), and two workshops with high school students in La Mojana region. In addition, we used the forecasts and historical climate information to contrast the narratives of the subsistence farmers.

The second location of our fieldwork was the bio-geographical region of La Mojana, the interior delta of the Magdalena-Cauca rivers basin. In this region, we planned to meet fisherpeople, rice growers, and institutional actors in charge of the adaptation to climate change, as well as to conduct workshops with high school students. La Mojana is a region of wetlands and floodplains, regulated by the seasonal pulse of water from which communities have developed amphibious ways of life. Many changes, some intentional and not, to the landscape have occurred in La Mojana. For example, governments have attempted interventions to mitigate the “natural” floods by building flood walls, while rice and cattle production have inadvertently caused significant modifications to the territorialities of local communities through farming practices. More recently, the region has become more sensitive to climate change, experiencing catastrophic episodes of droughts and floods.

The interviews with coffee and rice growers, and with fisherpeople were oriented to understand how important climate change is in their productive activities, how people read the weather with biological markers, how they construct locally situated knowledge about climate, and the access and use they have for scientific climate and weather information. For the institutional actors (producers’ organizations and the regional organization of forecast and early warnings), the objective was to identify the strategies those organizations have to publish the information they produce: channels, presentation and scale of the information, and potential users.

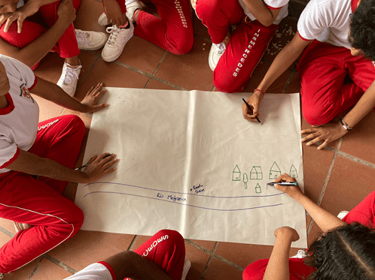

The student workshops were an ideal scenario to continue the explorations on locally situated climate knowledge among younger people. We performed 3 workshops with more than 70 students between the ages of 12 to 16. The workshops had four major activities:

1. Icebreaker and identification of population activity. In this first activity, we drew a line on the floor and asked the participants to step on one side or the other according to their answers to a series of questions. This activity allowed us to activate the participants, identify some characteristics (i.e. if they live in urban or rural areas, the occupation of their parents), and gave us some insights on their trust in the national organization in charge of providing weather information, along with some other biological markers that the subsistence farmers had mentioned in the interviews.

2. Direct questions about climate change and weather. We placed sheets of paper with questions like what is climate change, how do you know it is going to rain or what is El Niño, so the students could answer them directly, in groups.

3. Climate symphony. To teach the students the difference between climate change and climate variability, Laurel led an activity where students were split into groups and created a rhythm that is representative of one form of climate variability, such as weather, ENSO, or decadal variability. When the rhythms were established, the groups played their rhythms together to hear the climate symphony. To incorporate climate change into the symphony, the different groups were asked to slow down, speed up, louden, or soften their rhythms; however, the students learned that scientists are not fully sure what will happen to variability under climate change.

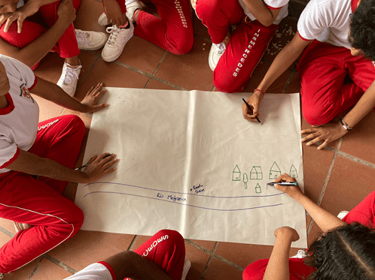

4. Social/collective mapping. In the workshops in Sucre (Sucre), we wanted to know more about the understanding of water and floods by the students. On a sheet of paper we sketched the main characteristics of the village, and we asked them to indicate the places which were generally flooded. This methodology was possible because the students had a deep knowledge of their town - which they were able to draw on a map - and indicated the main areas that would commonly flood during rainfall events. Moreover, we did the workshop in groups so students could share and complement each other's ideas to complete the map.

The team is more than the sum of its members

The joint work between two human geographers and a climate scientist has been very informative and unique because it has allowed us to have a wider perception of the complex topics of climate change and climate knowledge. As we discussed several times during CATER school, interdisciplinary research really allows us to address the complexity and to understand more comprehensive phenomena. It has invited us to focus on aspects that we didn’t take into account before.

In addition, teamwork is not only about knowledge but also about different methodologies and life experiences. For example, Laurel’s experience with music was invaluable to designing the symphony of climate activity, and Carolina and Flora experiences in the Huila and La Mojana regions allowed the team to tailor the interviews, using local references, words, and even social conventions.

Our insightful results

Lack of trust in regional and national climate information: In general, there was very little trust in climate information produced by scientists and forecasters on the regional and national levels, such as from the National Meteorological Services of Columbia (IDEAM). Many of the farmers, especially those in the Huila region, used local and indigenous knowledge to predict upcoming rainfall events, as they did not trust that the nationally produced forecasts would best represent the observed rainfall and microclimate in their particular location. In some regions, farmers would Google or use the weather apps on their phones to identify the upcoming weather forecasts, but forecasts longer than 14 days out were not regularly used. When asked what their preferred forecast would be (in an ideal world), the farmers were mostly interested in obtaining forecasts of one month out and perhaps one season (3 months).

In the Sucre region, large rice and cattle farmers had access to and used seasonal and other climate forecasts; however, subsistence farmers did not have access to such information and did not know it even existed; however, they did express interest in having access to such information. The lack of access to climate information in the region suggests a failure of the regional meteorological services to effectively disseminate climate information to the local community. However, one rice miller in the Sucre region expressed the greatest trust in national forecasts, claiming the forecasts to be correct 70% of the time, suggesting there must be some channels of climate information communication that are reaching the farmers and are found to be reliable.

Generational change in climate knowledge: In both of the study regions, there were distinct general differences in the use of climate information for small scale subsistence farmers. For individuals belonging to older generations (individuals >50 years old), indigenous and local knowledge passed on from elders was primarily used to make decisions about crops and growing season. For young and middle aged farmers (50 > 20 years old), some indigenous and local knowledge was used; however we did see some usage of forecasts from the internet. When talking to children in the schools, many of them knew about climate change and how it is impacting their community, but they were not familiar with forecasts or any additional climate knowledge, such as climate variability. However, many of the adults we spoke with were familiar with ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) and its phases (El Niño, neutral, and La Niña) and explained that knowing the current or upcoming ENSO phase helped them to determine how to manage their farms.

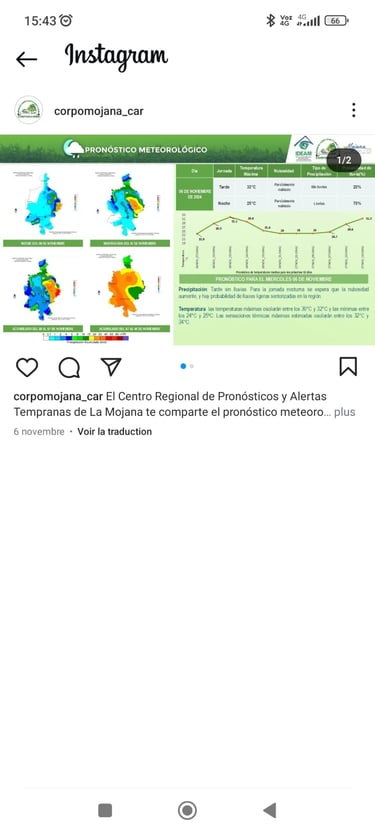

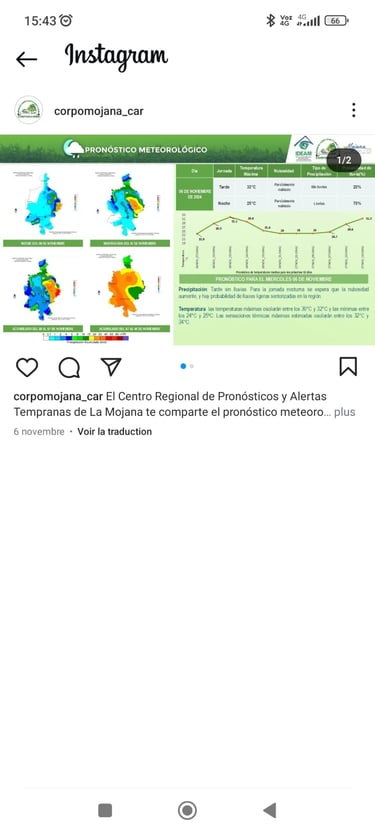

New channels: Another result was that all the actors (institutions and individuals) seem connected by WhatsApp and some by Instagram, where they receive a translation of technical climate information in more accessible language. The formats of the information are variable, such as periodic short boletins or daily voice notes. However, we noticed inequalities between those who were able to receive this information and those who were not, specifically subsistence farmers, who are not part of the climate information networks, association networks or the institutional programs are not part of the groups.

The use of WhatsApp and Instagram is a practical way to communicate information to a wider range of people, but it can also be very exclusive for people who don’t have cell phones or are not connected to any network.

Role of producers’ associations: Producers associations (coffee and rice) are a key actor in the production and dissemination of climate and weather information, in part because people trust them more than governmental institutions. However, their reach is quite limited, since the information they produce only reaches their associates. The smallest producers - who are the most vulnerable to climate and weather phenomena - normally are not members of such associations.

Alterations of biological cycles make traditional knowledge less reliable: Climate change affects not only the productivity of coffee and rice, or makes fishing harder. Changes in temperature and rain patterns also affect the vital cycles of animals and plants, and with that the biological signals people use to read their environment. We note that people no longer trust the traditional markers as before, they don’t believe in the song of the carrao bird announcing the rain. However, new locally situated knowledge is built from a systematic and contextualized observation of the new patterns of animals and plants.

For the current and future CATER students:

After our time in the field, we would like to stress how imperative it is that CATER school participants and faculty leave their labs and go into the field to understand the demand for climate information and services. With how differently farmers responded to or were interested in climate information, even within one country or region, it is evident that a one-size-fits all initiative through a grant or research project is not going to sufficiently meet the needs of a majority of individuals.

Acknowledgements: This trip was partially funded by the CATER School and we thank the PIs of the project for making this fieldwork possible. Additional funding was provided by the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University for Laurel’s travel to Colombia and from the French Institute of Andean Studies and the Doctoral School 122 of Sorbonne Nouvelle University for Flora and Carolina.

Table 1. Interviews in the Huila

Table 2. Interviews in the La Mojana

Images below:

The research team traveling by boat in the lowlands. Photo: Laurel DiSera

Map of the areas of study.

The Huila mountains and coffee crops, in Javier San Juan’s coffee farm (Pitalito). Photo: Flora Lecomte

Municipality of Sucre (department of Sucre) in La Mojana. Photo: Flora Lecomte

First workshop in San Marcos (Sucre) in La Mojana. Photo: Laurel DiSera

Second workshop in Sucre (Sucre), in La Mojana. Photo: Flora Lecomte

An example of the weather/climate information provided over Instagram from the Regional Center of Seasonal Forecasts and Alerts of La Mojana.